Contents

Introduction

Okay, so let's say that you

have some Apollo Program documents in your possession, or

even—wonder of wonders!—an AGC program listing. You've read

the Virtual Apollo website and seen the plea that you donate

digital images to the project. You're that rarest of

people, who actually look ahead to future generations and think

this would be a valuable thing to do.

But ... how do you do it?

Well, if the document you're working with is small—say, 150 U.S.

letter-sized pages—most of you won't really need much advice from

me. Even the cheapest scanner or digital camera will do the

trick. (It may be slow and painful, but that will just help

to give you a sense of accomplishment!) The advice I'd give

in that case is simply this:

- Check carefully before doing anything that your document

isn't already online somewhere. While I'm an assiduous

collector of this info, I'm not necessarily able to tell you

accurately what's available and what's not. Of course, if

you have a different version

of something that's

already available, or if you can make it more legible or better

in some other way, go ahead and digitize it anyway!

- The document usually will have a binding on it, and you may

be tempted to scan it with the binding in place. You can

certainly do that. However, the document will suffer

excessive wear, the scans will be relatively poor, and it will

be a lot more effort for you. In almost all cases it's

easy to remove the binding before making the copies, and to put

the binding back afterward.

- Don't worry too much about getting the scans into the same

form we use to publish them online ... PDF, JPG, TIFF,

etc. Whatever you send us, we'll preserve the raw images

as-is and turn it into an appropriate format for

publishing.

- Don't worry too much about things like color vs.

black&white, dots per inch, etc. Worry about

legibility. Make sure that in whatever images you create,

the text and diagrams are readable, even if you need to zoom in

when viewing them to do so. If you need to use higher dpi

in pages that are diagrams than you do on text pages, then

please do so.

- Don't worry about foldouts that are too big to fit on your

scanner. Simply scan them in several passes and provide

several JPGs or TIFFs for them, and we'll digitally recombine

them in a complete foldout.

- Do not skip blank pages. We have know way to know

that they're supposed to be blank, and will think that a page

is missing. Always double-check to make sure that every

page is present.

- If you are providing PDF, do not apply optical character

recognition to it (PDF). Let me worry about that

part.

- Simply email me (Ron Burkey <info@sandroid.org>) the

finished PDF or a zipfile of the JPGs or TIFFs ... or send them

as a tarball or a rar archive, or using whatever archiving

method pleases you.

On

the other hand, let's suppose

that you're lucky enough to have a lot of Apollo materials, and you

recognize that the simplistic scheme mentioned above is going to

take forever to

accomplish. In that case, you need to put a little more

thought ... and possibly money ... into the digitization.

If money is the obstacle, contact me and I can probably defray

expenses.

On

the other hand, let's suppose

that you're lucky enough to have a lot of Apollo materials, and you

recognize that the simplistic scheme mentioned above is going to

take forever to

accomplish. In that case, you need to put a little more

thought ... and possibly money ... into the digitization.

If money is the obstacle, contact me and I can probably defray

expenses.

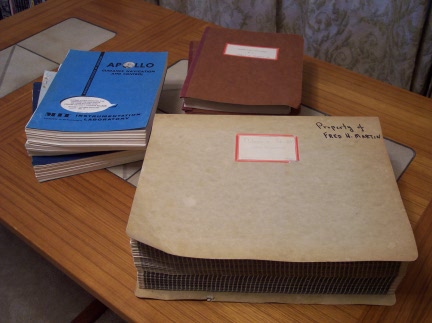

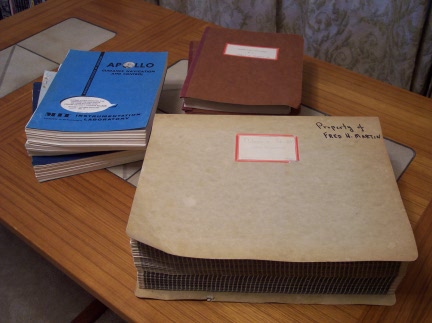

In the photo at right, which you can click to enlarge if you'd

like to admire it, is a stack of documents sent to me by original

AGC developer Fred Martin. The large pale-green document in

front is the AGC program listing of Apollo 8; it's about 1600

pages of 11"×15" fanfold paper. Behind it, the brown

document in two volumes is the Command Module AGC program listing

of Apollo 9; it's about 1700 8"×10.5" double-sided pages,

with an easy-to remove binder. Next to that is a collection

of miscellaneous documents—the top document being a portion of

the Apollo 10 GSOP—perhaps another 1500 pages of 8.5"×11"

double-sized pages, with either easy-to-remove bindings or

staples. That's a stack of documents that you'd be lucky to

have, but which would certainly be far beyond the capabilities

that most people have at their disposal for digitization of

documents or images in any reasonable amount of time and

effort.

In a case like this, I'd usually just recommend letting us do the digitization

for

you, and of course that's exactly what Fred did. But

perhaps you've got more time at your disposal and are keener to

volunteer the time and energy to do the digitizations as a

do-it-yourself project? What then? (By the way, Fred

helped write the software and then preserved it for 40 years, so

that's enough expenditure of time and energy as far as I'm

concerned. Thanks, Fred!) I don't know that I can

really give any definitive advice, but I can show you what I did,

and that may at least serve as a guide to whether you want to do

it or not.

A Note on File Formats ...

If You Care

I've gotten some flack for suggesting in some of my

recommendations below that JPG is a good file format for

preserving the scanned images of these documents. The

complaint is that JPG is a "lossy" storage format, while some

other file formats like PNG or TIFF are "lossless". For a

digital camera, an image in RAW format is even better than PNG or

TIFF, since in addition to being lossless it facilitates certain

types of image post-processing that PNG or TIFF do not.

What that means is that while PNG doesn't degrade the imagery,

JPG does degrade them ... but probably not in any way that is

perceptible. In other words, lossless is GOOD, and lossy is

BAD, but not terribly bad.

The problem is that the lossless PNGs may in some cases be

incredibly larger than JPGs of the same source material. For

example, consider the

AGC program listing of the SOLARIUM program, used on the

unmanned Apollo 4 and Apollo 6 missions. JPGs of the

individual pages of this program listing are around 6 MB each,

while PNGs and TIFFs of the same pages are around 45 MB and 50 MB

each. And while the JPGs are (in a theoretical sense)

certainly degraded, you can display the JPG right next to the PNG

and zoom in to any magnification you care to use, and will never

be able to see that degradation with the naked eye.

On the other hand, if the document you want to scan is very

clearly sharp black print on clean white paper, then there won't

be too much size penalty in using PNG rather than JPG.

Indeed, the PNGs may even be smaller than the JPGs.

So my general recommendation is that if you have the option

of choosing the storage format of your images, and if

PNG images aren't too much bigger than JPG, then by all

means use PNG. Otherwise use JPG. (And if your

equipment produces JPGs, leave them as JPGs; converting a

JPG to PNG after it has been created is of no use at all, since

any data loss will already have occurred at the time the images

were created.)

My Current Scanner

Recommendation

If money is no object, the best current solution is

to use what's known as an "overhead scanner" or "book

scanner". That's a device that allows the document or printout

to lay flat on a desk or table-top, with the built-in camera

pointing straight down at it.

If money is no object, the best current solution is

to use what's known as an "overhead scanner" or "book

scanner". That's a device that allows the document or printout

to lay flat on a desk or table-top, with the built-in camera

pointing straight down at it.

When I say "money is no object", I don't mean that these devices are

necessary terribly expensive — though "expense" is obviously

subjective — but merely that not everyone has one sitting around the

house already. And not everyone feels like spending money to

make scans for somebody else!

At any rate, if you have one of these, or access to one, it's the

best way to go. If, for example, you pay to have the Internet

Archive scan material for you, this is the kind of device they use,

albeit a much fancier and more-expensive one than the kind somebody

like me uses (as seen in the photo at left). Book scanners

have the great advantage of being very fast and simple to use, being

absolutely non-destructive to the material being scanned, and

typically come with software that "flattens" the imagery so that you

don't have to take a lot of pains to squash the material flat.

All of the document digitization I've done in the last couple of

years has been done with a device of this type.

The last Apollo

fanfold program listing I scanned was also done with a book

scanner, though admittedly when scanning a fanfold listing it helps

to augment the setup with a bit of extra do-it-yourself

rigging. For example, I threw together a stand to support the

scanner a little above the top of the desk, so that I could feed the

pages through, onto the black pad, underneath the

scanner. If anyone's interested in the details of that, drop

me a line and I'll write up a more-detailed description, with some

photos.

But as I say, most people are not in the position to use this

recommendation, since they may have a digital camera or a cheap

flatbed scanner sitting around, but don't have a book scanner.

If so, the following sections have my older recommendations on the

subject. There are really two different cases, and they need

to be handled

completely differently. The methods used for one aren't

suitable for the other, or at least not without some

re-imaginings ... which is to say, not without some ideas that

have occurred to me but which I haven't actually tried

myself. The two different cases are:

My Old

Recommendation: Digitizing a Fanfold

Computer Printout

A computer printout of an AGC program

listing will typically be on oversized (11"×15") fanfold

paper. In most cases, it will be on extraordinarily thin,

floppy white paper with black lines, although in some cases the

computer paper has green and orange bands on it. All of

these points make such a listing difficult to deal with.

First, as a theoretical proposition, it might be possible to scan

such a document using a tabloid-sized (11"×17") flatbed scanner,

and very carefully (so as not to tear the pages apart) slide the

pages across the scanner one at a time. If you did so, I

dare say the results would be exceptional, and would be far

better than the method I'm actually going to recommend

using. I have such a scanner myself, but the scanner itself

is so poor and so slow that it would be unthinkable to actually

use it. Aside from price, the problem is speed. So if you were to

purchase such a scanner, you find that it was unusable if it took

(say) 1 minute to scan each page. Most scanner models do

not give you a specification for the scanning speed, and that

usually means slow ... slow ... slow. If you have occasion

to try this approach let me know the details (including the

scanner model) and how well it worked out. At the present

time, not having tried this approach myself, I'd probably

recommend the Epson GT-20000 ($1500) scanner.

But putting talk of scanners aside, the method we have used at Virtual AGC

&

friends is a digital camera. A digital-camera setup was

used for obtaining images of AGC software for Apollo

4, Apollo

8, Apollo

11 CM, Apollo

11 LM, and Apollo

15-17 CM. If you actually look at the images so

achieved, you may not be impressed with the quality.

Indeed, those images are not even the raw images from the

cameras, but were post-processed to make them look better!

But realize that the goal was not be able to make an image that

you could print out that would be indistinguishable from the

original hardcopy. Rather, the goal was to achieve

legible text, with

minimal document wear,

and a reasonable expenditure of

time. And I think a reasonable compromise has been

achieved between those goals. If your goal is to make

something indistinguishable from the original, go back to the

last paragraph and think about scanners again.

One great advantage of the digital camera approach is that the

equipment cost is very cheap, since most people have an

acceptable camera already, or else can purchase one for a very

modest cost. How good a camera is needed? As you'll

discern from the following table, the "features" that most people

would choose a camera for are not necessarily good for

our purposes. The

best camera for the job may well be the one in which you can turn

off the most "features". Fancy optics and what-not?

Forget them, as they'll not help you one bit for the

digitization!

The

Ideal Camera

|

Minimally Acceptable Camera

|

- 5 megapixels or greater

- Tripod-mountable

- AC adapter to run from 120V rather than from

batteries

- Manual mode in which auto-focus can be turned

off

- Means of setting the white-balance as desired

- Means of setting the exposure as desired

- 2-3 exposures per second.

- 16 GB or greater storage—for example, 16 GB SDHC

card—accessible without unmounting the camera from the

tripod

- USB 2.0 interface, accessible without unmounting

the camera from the tripod.

- Remote control

|

- 4 megapixels or greater

- Tripod-mountable

Examples: practically any new camera in the

$100-200 range.

|

Most of the criteria listed for the "ideal camera" are really

productivity features that allow you to attain a better rate of

speed in the photography. The best sustained rate it is

possible to achieve using the method I'll describe is around 8-10

seconds per page, allowing an entire AGC listing to be

photographed in about 5 hours. Any productivity feature

that is lacking makes the process take longer, although there are

tradeoffs between some of the features so that if you have one of

the features you might not need some of the others. The

remaining criteria are for the purpose of maintaining

shot-to-shot consistency, but obviously the importance of that is

debatable.

The cheapest known example of a camera having all of the features

(at least as options) listed above is the Panasonic Lumix DMC-G1,

which presently (8/2009) costs around $800. I have also

used the Panasonic Lumix DMC-FZ5, which is an older, now

obsoleted, less expensive ($350) camera that lacks several of the

productivity features mentioned above. Both were very

acceptable. The better camera produced better results, but

that may be because of improvement in my understanding of white

balance more than any other factor. However, working

without the productivity features made the work go much more

slowly with the older camera, particularly in so far as

extracting the photos from the camera was concerned.

Let's go through the criteria one-by-one to understand whether or

not they'll be important to you:

- 5 megapixels or greater—You may think that the more pixels

the better. Well, yes, that's obviously true. The

higher the resolution you want to use, the happier we'll be to

get them. But the images are presently crunched down to

about 1400×1000 pixels for publication online, so most of the

pixels from even a 4 megapixel image are going to be thrown

away. The advantage of using 5 megapixels as opposed to

(say) 3 megapixels is that you don't have to worry as much

about getting an optimal zoom-in when you're setting up for the

shoot. We'll crop off anything we don't like before we

publish the images anyway, so you might as well leave a little

margin around the page when you take the photographs.

- Tripod-mountable—Self-explanatory, I think.

- AC adapter rather than batteries—You're going to take about

3500 shots for a typical AGC program listing. A typical

camera's batteries may give you 200-500 shots. Obviously

you can recharge batteries and change them periodically.

This requires a lot of extra time, but more importantly it

requires you to remove the camera from the tripod and to lose

any setups such as zooms you've made. The re-setup after

the battery has been replaced takes time, and you won't be able

to do it exactly the same every time, so different blocks of

pages will be inconsistent in size, lighting, angle, etc., with

each other.

- Auto-focus off—Auto-focus takes extra time on every shot,

but it also means that each shot will be different in

appearance, since the focus will be done a little

differently. With a cheap camera, most shots will be

in-focus, but some of them will be out of focus, and you won't

know that until you review the images later. It's better

to set up the focus once and to keep using it that

way.

- White-balance—Setting the white balance allows you to

compensate for the color of the lighting used, such as natural

light vs. incandescent lights. You may think that this

doesn't matter—I know that I

did—but it affects the color of

the page background, and that in turn affects the ability to

post-process it easily, which in turn affects the final

contrast of the posted images. So if the white-balance

isn't compensated properly, the background will be darker than

it needs to be and the text will be lighter than it needs to

be.

- Exposure—Same problem as with auto-focus, except that it

usually expresses itself in an inconsistency in brightness from

page to page. Often the even pages will be at a different

brightness than odd pages.

- 2-3 exposures per second—In the method I'll suggest using,

most of your time is

spent in manually changing from one page to the next.

Taking 2 or 3 shots of each page takes little more time than

taking a single shot, but greatly lowers the odds that you'll

have to go back later (after reviewing the images) and reshoot

any of the pages.

- 16 GB or greater storage—For an AGC listing, the

recommended method will require just over 8 GB if two shots are

made of every page, and just under 16 GB if three shots are

made. If the camera has a great enough capacity to store

the entire shoot, it saves the time of stopping in the middle

of a shoot to download images and/or to re-setup after changing

SD cards.

- USB 2.0—Actually, the 16 GB criterion and the USB 2.0

criterion are really mutually exclusive, in that you don't have

as much need for the one if you have the other. The point

of the USB 2.0 interface is that if you don't have big enough

internal storage in the camera to hold the entire shoot, you

can download whenever the camera fills up without having to

take the camera off of the tripod and do a re-setup

afterward. USB 1.0 is workable, but (for example) takes

about 40 minutes to download from a 2 GB SD card, so it adds

something like 50% to the total photography time just for the

downloads. In contrast, the download time using USB 2.0

is negligible. Similarly, if the SD cards can be removed

without having to remove the camera from the tripod, then USB

might not be needed at all.

- Remote control—This is really just a nice-to-have.

With the method we're going to recommend it's not really

needed, it's very nice to have. It allows you to work

without touching the camera, which means that a much

lighter-weight tripod can be used (good for the pocket-book and

very good if you have to carry it around) and that you don't

have to worry so much about bumping the camera as you move

around.

Now, what will you need in order take the pictures?

- The camera, of course.

- A tripod—by which I mean a regular tripod, not a table

tripod. A heavier, sturdier tripod is better, but on my

last shoot I used a sleazy tripod that Circuit City gave me for

free with my camcorder. And if you have a remote control,

the quality of the tripod doesn't matter at all.

- A table.

- 2-3 60W lamps ... maybe. Depending on the ambient

lighting and how well you are able to configure you camera, you

may not even want to use any extra lighting at all.

- A few pages of white paper.

- Some scotch tape.

- Some books.

- A moving box.

What? Some books? A moving box? You'll

understand in a moment.

First, let me show you the setup I actually use, which will be a

little different than yours (no moving box!), because a friend

has been kind enough to create a special-purpose copy-stand for

me. What you see in the photos below, which you can click

to enlarge if you like, is a table with my laptop computer and

the white custom-built copy-stand I mentioned on it.

Perhaps 6 feet in front of the table—the exact distance isn't

critical—is a tripod with the camera on top of it and two lamps

clipped to the sides of it. Because it happens to be a very

light-weight tripod, and it is atop carpeting, some books have

been placed underneath the legs of the tripod to hopfully reduce

settling and vibration. The various cables you see are the

power cords of the computer, the camera, and the lights, and the

USB cable (going through several extensions) from the camera to

the laptop computer. The fanfold printout, for what it's

worth, is the Apollo 8 AGC program listing. At the

beginning of the photo shoot, it was completely on the floor, but

at this point I've already advanced one page at a time through

perhaps 1200 pages, and the pages that have already been

photographed are stacked up behind the page being

photographed.

There are a few of important points to note that may not be clear

from the photographs:

- The binder holding the program listing had to be removed

for this process to work. It was put back on

afterward. The program listing suffers no damage whatever

from either the binder removal or from the photography if

you're careful.

- The lamps clamped to the camera tripod are simply normal

lamps—not special photographic equipment—that just happen to

have clamps rather than supporting bases. I rely on

ambient lighting along with these lamps. The lamps cost

me $10 apiece at Target. Floor-standing lamps would work

also, but note that we're trying to get the lighting as even as

possible across the page being photographed, and the more

oblique the light the less even it will be. Also, as

you'll see in a moment, you may have to be careful with

floor-standing models to keep from knocking them over. I

happen to be using 60W-equivalent compact flourescent bulbs

rather than actual 60W incandescent bulbs, simply because it's

not as hot that way. As I mentioned above, you may not

even want the extra lighting at all, and in my most-recent

shoot (Colossus

237) I did not use them. Don't be fooled into thinking that

because the page background is gray rather than white you need

more lights!

- The copy-stand is at a slight angle from vertical, and the

camera is actually angled downward a little to be at

right-angles to the copy-stand. This angling

unfortunately limits the distance between the copy-stand and

the camera—in other words, you can't get the camera very far

away—but it has the important purpose of helping the printout

to lay flat against the copy stand. If the copy-stand

were vertical, the paper would have a tendency to waft around

in every little breeze, not only causing the pages to be in

motion, but also for there to be a shadow-casting gap between

the paper and the copy-stand.

- The perforated edge between printout pages is placed

exactly at the top of the copy-stand, which is something that

can be done very quickly and accurately when advancing the

paper.

- There is a small mark drawn on the copy-stand to show where

the edge of the paper is supposed to go, and it's very easy to

align the paper with this mark.

- But

most important of all, to take a picture you have to

press the camera button downward,

which is the direction

in which the tripod support provides the greatest stability, so

there is very little camera motion when you press the

button. That means that while a remote control would be

nice, it is not needed.

When people talk

about using a digital camera to photograph documents, they

normally think of the document as laying flat on a table and

the camera looking down from above. This has many

disadvantages compared to the scheme I'm advocating, but the

principal disadvantage is that the camera would be at right

angles to the tripod, which is a very unstable setup, prone to

a lot of camera movement, when the camera button is

pressed. If you have a remote control for the camera,

this factor isn't important at all, but the vertical

arrangement of the paper still allows easier paper movement

than a horizontal arrangement.

Even though I don't appear in the pictures at all, the

technique is very simple: I step forward and move the paper

up by one page, aligning it properly, then I step back out of the

light and press the camera button. Then repeat. I

suggest taking 2-3 pictures for each page, since it takes 6-7

seconds to advance the paper and only a second to take the

picture, so (timewise) extra pictures are essentially free.

I'd also suggest doing a test run of 50 pages or so to make sure

you're doing it right before photographing 1700 pages!

For the camera setup:

- If you have a choice of file formats (TIFF, JPG, etc.), I'd

recommend using JPG.

- If you have a choice of image quality, choose whatever

format gives you JPG images that are roughly in the range of

1.5-2.5 megabytes. This doesn't have to be very

exact.

- If you have a choice of turning auto-focus OFF, do

so. Focus the camera once, at the beginning of the shoot,

an let it focussed the same way throughout.

- If you have a choice of white-balance and exposure,

experiment a little until you get some test shots that look

good to you.

- Turn off the flash.

- ... and if you know anything about photography—I sure

don't!—you'll undoubtedly figure out some other

improvements. Just remember, though, if you spend 20

hours experimenting for a 5-hour shoot, and you don't have more

of the same kind of thing to photograph in the future, you may

be overthinking it!

Now of course, you probably don't have a custom-built copy

stand. The custom-built copy-stand is great for me because

it folds up and is light-weight, and I usually have to travel to

take these photos, but you can get results of just as high

quality without it. What you do is to take a sturdy

cardboard box, and place it where the copy-stand would have been,

at the edge of the table. Put a book under the front edge

of the box to tilt it a little. Fill the box

with books or other weights so that it won't move around.

Tape some white paper at the front to make the front surface of

the box white. Make a mark on the white paper to show where

the edge of the printout is supposed to go. Voila!

Instant, cheap copy-stand! I have taken hundreds of photos

using this exact moving box :), and believe me that the quality

of the photos is identical to what they are with the fancy

copy-stand.

When you're all done photographing—or before, if you're insecure

:)—pull the photos from the camera into your computer, and step

through them to see that you have at least one legible picture

from every page, then send them to me.

My Old

Recommendation: Digitizing a Normal

Document

A "normal" document that is just a stack of pages in

a binder requires a very different technique than a fanfold

document such as a program listing, and depending on the

equipment at your disposal may be very much faster to digitize or

very much slower. Several digitizing methods are discussed

below. Understand that no matter what method you use to

digitize the document, you are going to be better off removing

its binder and restoring it afterward than trying to digitize

with the binder in place. In the three sub-sections below,

you should be able to determine relatively quickly if you can use

that method or not, therefore quickly move to the next section if

need be.

The

Convenient Way

The most convenient way to digitize a normal

document, if you have the equipment at your disposal to do so, is

to use a scanner with an automatic document feeder (ADF).

It's also the priciest method if you have to purchase the

equipment yourself, but many workplaces have suitable equipment

available if they will allow you to use it. If the

documents you are digitizing don't belong to you, you may not be

allowed to use a

document feeder. For example, the National Archives was

fine with me wanting to scan documents on a flatbed scanner, but

had rules against automatic document feeders. At any rate,

if you don't have access to such a scanner, or wouldn't be

allowed to use it, advance to the next section.

I do enough document scans that I actually thought it was worth

my while to purchase a fairly high-end scanner, an Epson

WorkForce Pro GT-S80. This gadget has a 75-page feeder, can

pull through 40 pages per minute, and can scan both sides of the

page at once (so that it effectively scans 80 pages per

minute). It's not cheap. On the other hand, I also

have an HP R60 multi-function device (printer/scanner/fax) with a

25-page feeder, that can probably pull and scan 1-2 pages per

minute. It wasn't cheap, either. So there's a very

wide range of performance, and none of it is cheap. But of

course, if there's a document feeder the digitization process can

run unattended and it doesn't really use up any of your time,

regardless of the speed.

Most scanners do not specify a scanning speed, and with good

reason ... they're very, very slow. The reason for this is

that scanners for personal use are basically optimized for

scanning a small number of photographs at very high quality, as

opposed to a very high volume of documents at fairly low

quality. Scanners which are optimized for the latter are

identified by the buzzword "document scanner" as opposed simply

to "scanner". Document scanners are optimized for 200 dpi

black&white scanning, and the speed specification relates to

a 200 dpi b&w configuration. That's the setting I

typically use myself, except in rare cases of very small

print.

Other than the price, the only real drawback of the scanner with

ADF is that there is a very small chance of a paper jam that

could conceivably damage your document. (That was the

reason for the National Archives' rule against ADF.) Having

scanned many thousands of pages using ADFs, I don't believe

that's something to worry about, but it's something you might

want to test out by scanning dummy documents before scanning real

documents. A lesser drawback with a very fast machine (such

as my scanner) is that it scans the pages so fast that there can

be a pretty big variation in the alignment of the pages.

:)

The Safest

Way

If a scanner with ADF can't be used, a flatbed scanner

may be the next-best option. I call it the "safest way",

but I don't really believe it's any safer than ADF since humans

are no more perfect at handling paper than machines are.

The principal difficulty with a flatbed scanner is, as described

in some detail in the prior section, that they are typically

very, very slow. For example, scanning a single page might

take 45 seconds. Without an ADF, that 45 seconds, times

however many pages there are, comes right out of your lifespan

and probably won't be replaced, karma notwithstanding.

The irony is that old scanners which provided a mere 150-600 dpi

rather than the modern photographic thousands of dpi were often

much faster. With my old HP ScanJet 2C that's over ten

years old, I can sustain a throughput of about 10 seconds per

scan at 200 dpi b&w. I used this method for scanning

many thousands of pages at the National Archives.

At any rate, you can figure it out for yourself whether the

flatbed will work for you. Scan a few pages, time it,

extrapolate to see how long it will take to do the entire job,

and then decide if that fits into a reasonable budget.

A

Re-Imagining

One thing I haven't tried,

but which may be

worth considering is to use a variation of the digital camera

methodology described earlier for fanfold printouts. If

the same method was used, except that a lip or clip or magnets or

some other trick was added to added to allow the copy-stand to

hold a single page at a time, you could probably digitize

documents at a rate of about 10 seconds per page. But as I

say, it has never been tried, that I know of.

Getting the

Digitized

Documents To Us

The size, in bytes, of document scans or

photographs is typically quite large. If you can package

your scans in small chunks—say, 10-20 megabyte zipfiles—you may

be able to email them to me one at a time.

Another very good option is to use an online storage space such as Google Drive or Dropbox to store the images,

and then just send me a link to them.

You can also physically mail me DVDs or USB keys with

the data on them. Inquire by email for a physical shipping

address. Make sure you have backups of any data you send,

in case the ones being shipped are lost in transit! I'd

prefer not returning the DVDs or USB keys to you. If you

need shipping expenses or the cost of DVD-R or USB keys to be

defrayed, let me know the total amount and the method by which

you'd like the money sent to you.

Getting Us To Do It For

You

There are two basic possibilities for getting me to

do the digitizing for you, as follows:

If you ship documents or

AGC program listings to me, I will digitize any that aren't

already online, and then return the originals to you—or to a

museum, if you would prefer. Inquire by email about a

physical shipping address. I can defray the shipping

cost, if requested.

If you ship documents or

AGC program listings to me, I will digitize any that aren't

already online, and then return the originals to you—or to a

museum, if you would prefer. Inquire by email about a

physical shipping address. I can defray the shipping

cost, if requested.- I can come to your location to perform the

digitization. However, I am only willing to do this if

the benefit is very great, and if you are willing for me to use

the digitization methods I've outlined on this web-page.

As far as I know, the only cases in which I would consider the

benefit very

great are: you have previously-unavailable program

listings for AGC, AGS, or LVDC; or, you have a large quantity (thousands

of

pages) of previously unavailable documents. This is not

to say that I think small documents aren't valuable, just that

my time, safety, and convenience have value as well.

Besides, if I came to your location it would have to be

something that was scheduled months in advance.

As far as the notion of donating to a museum is concerned, if

you were interested I'm presently recommending the Research

Library of the Wings Over the Rockies Air & Space Museum

in Denver. In general a research library is probably

preferable to a museum as such, since documents have very

little sex appeal when considered as display items, but may

be profitably viewed for research if properly

supervised. The Virtual AGC project has no affiliation

with the museum, but has received very significant help from

the Research Library in the past, and that is the basis for

my recommendation. Obviously, there are many other fine

institutions which deserve consideration as well, if you have

some personal preferences in that regard.

Sadly, an important point to consider about shipping

documents, is that there is a non-zero probability that they

will be lost in transit, even if they are shipped by the

safest feasible means. The most popular methods of

shipping in the U.S.—namely FedEx, UPS, and the USPS—do not

publish their shipping-loss rates. If you google this

question, you'll find any number of meaningless personal

rants about lost packages, demonstrating that one or more of

these shippers are terrible. However, somebody got the

bright idea of looking at the insurance rates being charged,

and estimating the loss rates from the insurance

charges. On this basis, one can conclude that FedEx and

UPS are roughly equivalent to each other, and that either of

them is perhaps twice as good as the USPS. Alarmingly,

though, the package-loss rate would appear to be on the order

of 1%. By "on the order of", I don't mean exactly 1%;

perhaps it is 2% or 0.5%. But it is probably less than

10% and greater than 0.1%. (Figure it out for

yourself: FedEx and UPS charge something like $0.32 per

each $100 of insurance. So they must expect something

like a 0.3% loss.)

Now, when you're shipping a commercial item the loss rate

doesn't really matter, because if you insured the object

properly then in the worst case all you have to do is to

order another one. But when you're shipping a

one-of-a-kind object, you can't just order up a new

one. No amount of insurance can compensate for the

loss. So that's something you'll want to consider if

you decide to ship your documents to me.

And speaking of insurance, how much is reasonable?

Well, recent activity on eBay suggests that a typical Apollo

Program document may be worth about $300, so that's the

number I'll arbitrarily use when shipping items back to you

unless instructed otherwise.

This page is available under the Creative

Commons

No Rights Reserved License

Last modified by Ronald Burkey on

2021-01-15.

On

the other hand, let's suppose

that you're lucky enough to have a lot of Apollo materials, and you

recognize that the simplistic scheme mentioned above is going to

take forever to

accomplish. In that case, you need to put a little more

thought ... and possibly money ... into the digitization.

If money is the obstacle, contact me and I can probably defray

expenses.

On

the other hand, let's suppose

that you're lucky enough to have a lot of Apollo materials, and you

recognize that the simplistic scheme mentioned above is going to

take forever to

accomplish. In that case, you need to put a little more

thought ... and possibly money ... into the digitization.

If money is the obstacle, contact me and I can probably defray

expenses.  If money is no object, the best current solution is

to use what's known as an "overhead scanner" or "book

scanner". That's a device that allows the document or printout

to lay flat on a desk or table-top, with the built-in camera

pointing straight down at it.

If money is no object, the best current solution is

to use what's known as an "overhead scanner" or "book

scanner". That's a device that allows the document or printout

to lay flat on a desk or table-top, with the built-in camera

pointing straight down at it.

If you ship documents or

AGC program listings to me, I will digitize any that aren't

already online, and then return the originals to you—or to a

museum, if you would prefer. Inquire by email about a

physical shipping address. I can defray the shipping

cost, if requested.

If you ship documents or

AGC program listings to me, I will digitize any that aren't

already online, and then return the originals to you—or to a

museum, if you would prefer. Inquire by email about a

physical shipping address. I can defray the shipping

cost, if requested.