The Virtual AGC Project was not involved in the

AGC-restoration project described herein. But one of our

core developers did participate, and there is a certain synergy

between the restoration effort and the Virtual AGC Project, so I

think it is reasonable to give some information about the

restoration effort here. If you see something bogus here,

blame me and not the restorers!

As for this specific webpage, it is under construction and is

still somewhat incomplete at the moment. My intention is not

to provide an up-to-the-minute accounting of the progress of the

restoration, which I'm not capable of doing anyway, and so it will

stay incomplete until the restoration has been completed ... which

hasn't entirely happened yet.

Unless otherwise stated, all photographs are by Mike Stewart.

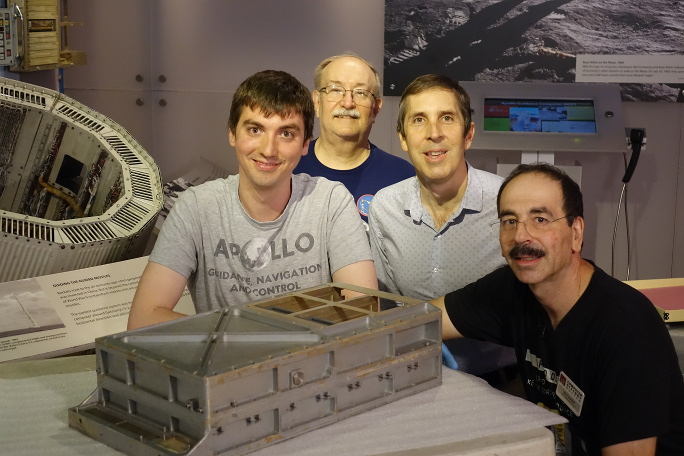

"The Restoration" is an attempt to power up and run one of the

original Apollo Guidance Computers. I'm told (in 2019) that

there is presently no other AGC in operation in the world.

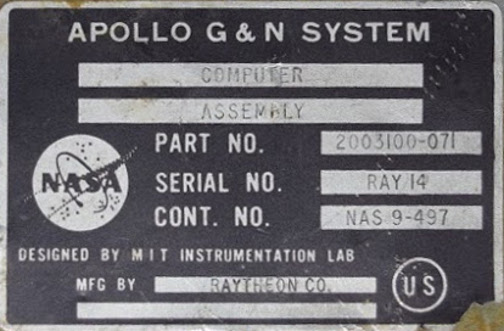

Specifically, this is an attempt to operate one particular Block II AGC:

Part number: 2003100-071

Serial number: (Raytheon) 14

Owner: Jimmie Loocke

To my recollection I've never had any personal contact with

Jimmie, but according to online information he worked in Project

Apollo as a thermal vacuum test technician for LTA-8 (Lunar Test

Article), among other things. LTA-8 was a LEM used only for

testing and qualification purposes. He was thus in a good

position years later to recognize the AGC when he saw it in a

warehouse of junk that was intended to be scrapped for recycling

purposes. After rescuing the AGC from its fate, the idea was

eventually conceived of actually restoring it and operating it.

Jimmie Loocke (seated) and Fred Haise

(light blue shirt) at SpaceFest IX.

|

Charlie Duke (center) and Jimmie

Loocke (right) at SpaceFest IX.

|

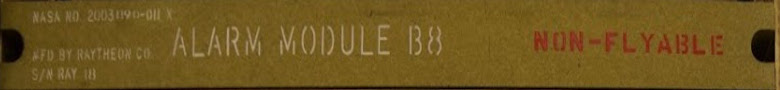

While this AGC never flew a mission, the restoration team

believes it was indeed used in the vacuum testing of LTA-8.

This seems like a reasonable hypothesis since LTA-8's G&N

(Guidance & Navigation) system, #602, did use an AGC p/n

2003100-071. Moreover, we have no record of that AGC model

having been used for any other purpose. In fact, the team has even

been able to come up with some photographic evidence of this

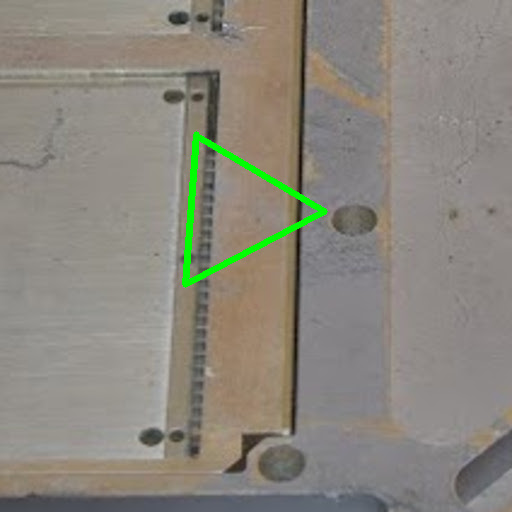

notion. Look at the photos below.

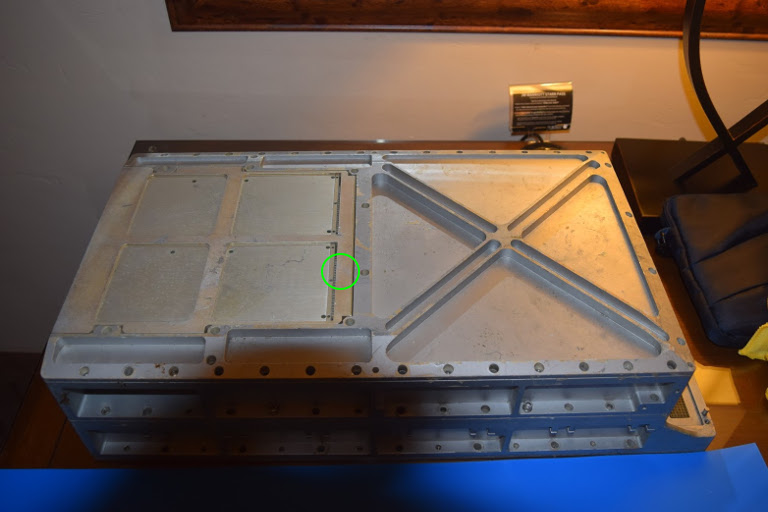

The restoration AGC |

The interior of LTA-8 just before thermal tests. The red oval indicates the where the AGC is mounted. (Not taken by Mike Stewart, obviously!) |

Like any physical object, the restoration AGC has various

discolorations, scratches, and so on ... "distinguishing marks",

which should tell us if the photos above match each other.

Of course, the restoration AGC is now 50 years older than it was

in the LTA-8, and we know that it has not been treated as

a national treasure in the meantime, so it's going to have a lot

more distinguishing marks than it used to. We'll just pick

one. The green circles in the photos above mark areas we're

going to zoom in on in the enlarged photos below. Look for

the triangular-shaped silvery area near the center of the

pictures.

|

|

In case you still can't see it, here's the same thing below, but

outlined in green to draw your attention to the feature I'm

talking about.

|

|

Which seems to confirm the team's thoughts: The restoration

AGC is indeed the AGC from LTA-8!

On the other hand .... it's very unlikely that this AGC was used

as-is in such vacuum testing. In any kind of official

testing, you typically want to use only devices whose

configurations are exactly as documented, so that the

entire testing configuration can be duplicated precisely later if

the tests need to be repeated for some reason or if problems are

discovered during testing. The restoration AGC, however, differs

in some significant ways from the documented configuration for AGC

p/n 2003100-071:

Incidentally, if that all sounded like gibberish to you, you

might find it valuable to look over my

explanation of the basic facts about the AGC's internal

structure before continuing.

In other respects, though, the AGC is exactly as we would

expect. Thus, a more accurate statement would be that this

AGC was originally used in LTA-8 vacuum testing, but that a number

of its circuit modules were subsequently swapped out and are no

longer original to the unit. That wouldn't be unusual, by

the way! Such repurposing happens all the time with

engineering units that have fulfilled their primary purpose and

have subsequently entered a second life as utility units. For

example, I'm told that the CURRENT SWITCH MODULE mentioned above

is one of a handful of modules in the AGC that had serious

internal failures; once upon a time, it seems that someone with a

broken AGC had raided the restoration AGC for its original working

modules, leaving behind the broken ones. Back in the day,

for engineering units that weren't going to be used on actual

missions, that would have been much more expeditious than

repairing the broken module. Repair is instead the

unfortunate task now left to the restorers. More on that

later.

In this case, though, it's downright convenient that some

of the circuit modules have been swapped, since it would have been

much harder for the restoration team to work with "potted" modules

than with the unpotted modules the unit now contains. In

fact, I wouldn't be surprised if the convenience factor hadn't

been part of the motivation the original Apollo engineers had in

swapping the modules in the first place!

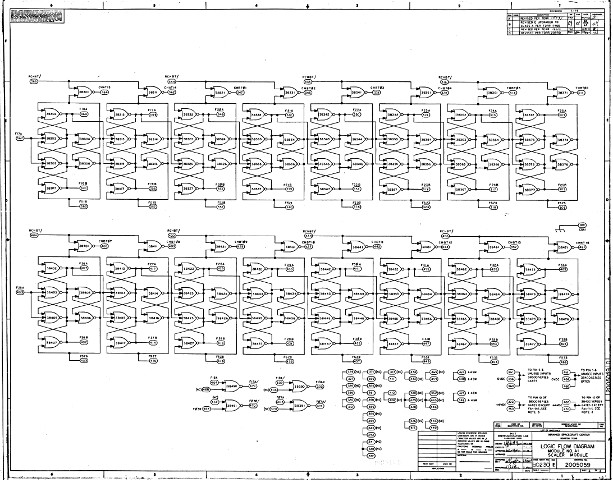

By the way, as I mentioned above, LTA-8 used G&N system #602,

of which we have the engineering

drawings. Of course, those include the drawings for

AGC p/n 2003100-071, but I've also split out the engineering drawings for AGC

2003100-071 separately as a convenience.

Having the engineering drawings is how I knew, for example, that

the p/n of module B11 was wrong. Well ... that and the fact

that we also have photos of all the circuit modules in the

restoration AGC, so we know exactly which part numbers and

configurations they have, and thus can compare them to the

engineering drawings.

By "engineering drawings", of course, I mean the mechanical

drawings and the electrical schematics. Other pertinent

facts we can glean from the engineering drawings for G&N

system #602 are that it would have used DSKY model 2003985-081

(whose drawings are included in the G&N engineering

drawings) and that the AGC would have been loaded with the

AURORA 85 software if the core rope modules had been present when

Jimmie found the AGC. Actually, to be pedantic about it, the

engineering drawings tell us only that AURORA software having a

part number of 2021101-011 would have been installed, while Table

3-IJ of document ND-1021042 tells us additionally that:

Other corroborating evidence comes from MIT's final report.

Chapter 10.1.3 of the report covers system testing using

AURORA. It mentions only AURORA 85 (of which it says 5 sets

of rope modules were manufactured) and an improved revision,

AURORA 88 (of which it says 4 sets were manufactured). All

things considered, it seems as though the only revisions of AURORA

for which rope modules were manufactured were 85 and 88.

Actually, both of these revisions were released and manufactured

in 1966, while the LTA-8 thermal-vacuum tests were nearly 2 years

later, so it's fun to speculate why 85 was used rather than 88 for

the testing. There's a

memo describing the differences, so I guess the answer to

that riddle would depend on whether any of the changes it

describes were relevant to the testing or not. If not, there

would have been no reason to use precious AURORA 88 core modules

when the more-plentiful AURORA 85 modules would work just as well.

Alas, we have no copy of AURORA 85 software, nor of AURORA

88. But we have something pretty close, namely AURORA 12,

and it can be run in the restoration AGC using the core rope

simulator. Don't be dismayed that the revision level is so

low, and thereby be fooled into thinking that it is a very early

revision compared to AURORA 85. There's reason to believe

that AURORA 12 is part of a development branch descending from

AURORA 88, and thus is much closer to AURORA 85 than would be

naively supposed. On the other hand, we have never come up

with a plausible theory as to where the confusing numbering as

"12" came from, so who really knows?

If you're interested, you can view AURORA 12 in a variety of

forms, including a

pretty-printed transcription to source code, or even run it

in our AGC simulation software. And have no fear, AURORA 12

is a software revision that would undoubtedly have functioned

adequately in LTA-8. Not to mention that it's the only

AURORA revision we have the actual source code for. A

significant fact about AURORA is that it includes a full suite of

self-test software ... the last AGC software version to do

so, since in later versions the self-test was greatly curtailed in

order to save precious memory. Thus AURORA was typically the

software used during Project Apollo itself to check out the AGC.

Of course, the question of what software should have

been installed in the restoration AGC and what software actually

was installed in the AGC the last time it had rope modules

are two different questions!

As it turns out, we're pretty sure that some revision of AURORA

was indeed the last set of ropes installed, but which don't know

which AURORA revision. That's a pretty sweeping statement,

considering that we don't have the original rope modules!

How could anybody know for sure? Well, the conclusion comes

from a clever forensic analysis by the restoration team, which

goes something like this: The first thing to note is that

the core ropes weren't the only type of memory in the

AGC. The core ropes, by definition, are manufactured in such

a way that they contain fixed patterns of data — i.e., the program

itself — which couldn't be changed by the AGC itself. But

the AGC also contained erasable memory, which it could both write

to and read from. Different versions of the AGC software in

the core ropes inevitably ended up having different patterns of

erasable memory usage when the software ran, so if you knew

exactly what to look for in erasable memory, you could treat the

patterns in erasable memory as a kind of "fingerprint" to

determine which program had been stored in the core ropes the very

last time the AGC had been in operation. (Assuming of course

that the erasable memory module hadn't been swapped out from a

different AGC in the meantime!) Perhaps most importantly,

the restoration team stored the entire contents of the erasable

memory module before they did anything that could possibly change

the contents of memory, so they were in position to use this

fingerprint information!

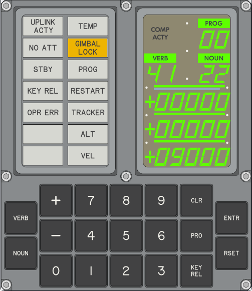

The specific pattern in erasable memory

that the the team looked at is the so-called DSPTAB.

It doesn't really matter what DSPTAB is, for the purpose

of this explanation, but in case you're interested, it happens to

to be an 11-word table in which the

PINBALL GAME BUTTONS AND LIGHTS subprogram keeps

track of what is stored in all of the DSKY's internal relays, so

that it knows not to waste time writing to those relays if the

values haven't changed. The important thing to us at the

moment, though, is that of all the many AGC software versions we

know, only AURORA locates DSPTAB specifically at address

0307 (octal) in erasable memory. And since the contents of DSPTAB

are themselves DSKY-relay values, there should only be certain

recognizable patterns stored in it.

The specific pattern in erasable memory

that the the team looked at is the so-called DSPTAB.

It doesn't really matter what DSPTAB is, for the purpose

of this explanation, but in case you're interested, it happens to

to be an 11-word table in which the

PINBALL GAME BUTTONS AND LIGHTS subprogram keeps

track of what is stored in all of the DSKY's internal relays, so

that it knows not to waste time writing to those relays if the

values haven't changed. The important thing to us at the

moment, though, is that of all the many AGC software versions we

know, only AURORA locates DSPTAB specifically at address

0307 (octal) in erasable memory. And since the contents of DSPTAB

are themselves DSKY-relay values, there should only be certain

recognizable patterns stored in it.

And indeed, that's what the team found: Stored at address

0307 in erasable memory was a set of relay patterns. The

image at right is a screenshot of a (simulated) DSKY into whose

relays the DSPTAB table is loaded. In other

words, what you see is the very last thing the DSKY displayed the

very last time the restoration AGC had been run back in the

1960's. A ghost of the past!

In fact, the forensic analysis of the contents of erasable memory

was much harder than I've made it sound, because as we'll see later, the erasable memory

module is actually broken ... a matter which gave the team a lot

of heartache before managing to work around the problem.

By the way, all the talk above about AURORA isn't meant to imply

that AURORA is the only software the restoration AGC can

run. In fact, it should be capable of running essentially

any of the Block II AGC software we have on our LUMINARY or COLOSSUS

pages. Actually, the team has told me that, in fact, they

had tested every AGC software version we have, and that all of

them did run fine on the restoration AGC.

The restoration team has made an ongoing series of videos about

their activity, thus gaining a measure of recognition both in the

online and real worlds. As I'm writing this, they are on

video part 11, and there will undoubtedly be more parts in the

future. Here is part 1:

Here are also some online articles about the restoration:

Suppose you were handed an AGC and told to get it

working. Since the AGC is a unique artifact that cannot be

replaced, you obviously don't want to damage it by drilling holes in

it, prying it apart, etc. Or at least, whatever you do to it

needs to be minimally invasive. Beyond that, though, the steps

involved aren't really much different than those an engineer needs

to take if they had designed a device themselves and needed to power

it up the first time. Under those circumstances, there's

always something that doesn't work and needs to be debugged.

Suppose you were handed an AGC and told to get it

working. Since the AGC is a unique artifact that cannot be

replaced, you obviously don't want to damage it by drilling holes in

it, prying it apart, etc. Or at least, whatever you do to it

needs to be minimally invasive. Beyond that, though, the steps

involved aren't really much different than those an engineer needs

to take if they had designed a device themselves and needed to power

it up the first time. Under those circumstances, there's

always something that doesn't work and needs to be debugged.If you're managed to get this far, you're probably truly

interested in the technical nitty-gritty. I might suggest

reading farther on Carl

Claunch's blog.

TBD

TBD

What the team found as they proceeded was that things were not

entirely rosy ... a little rosy, indeed pretty

rosy, but not perfectly so. Most of the circuitry still

worked! But not all of it, particularly among those modules

that had been replaced, presumably after LTA-8

testing. As I mentioned earlier, one reason that circuit

modules may have been swapped afterward is that after its primary

function (LTA-8 testing) had finished up, the AGC itself became a

resource: It could be used as a source of spare parts.

So if you were an engineer working with a different AGC and

something on it broke, no problem! Just replace the broken

module with a good (though likely older-model) one from the LTA-8

AGC! As long as the AGC you were working with didn't end up

in an actual mission, the fact that it had an obsolete (but

functional!) circuit module or two was of no consequence to

you. The unpleasant side-effect, of course, is that you end

up with broken circuit modules in the restoration AGC.

The team basically encountered only a few problems as they

followed this path, and one of those had nothing to do with actual

circuit breakage.

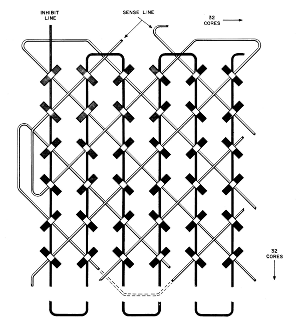

Erasable memory as it's supposed to be. (Click to enlarge.) |

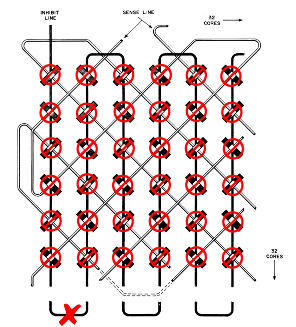

Erasable memory with a broken INHIBIT line. (Click to enlarge.) |

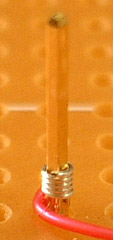

It may seem curious to you that I say the

connector pins used in the AGC were no longer available nor

being manufactured. Why don't I just say that the connectors

are no longer available?

It may seem curious to you that I say the

connector pins used in the AGC were no longer available nor

being manufactured. Why don't I just say that the connectors

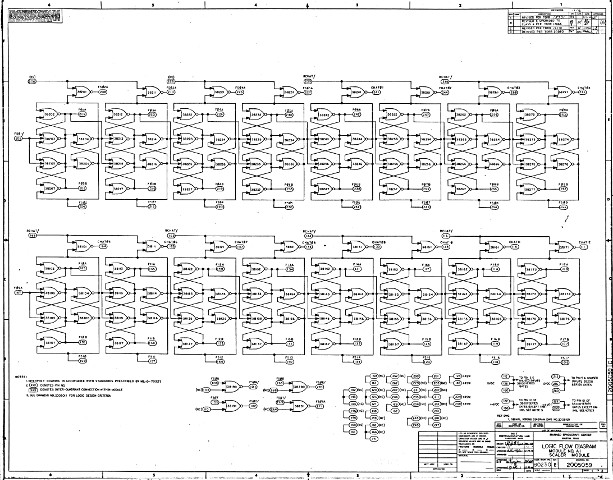

are no longer available?  Scaler module A1 electrical schematic, top side. (Click to enlarge.) |

Scaler module A1 electrical schematic, bottom side. (Click to enlarge.) |

TBD

Which finally brings us to the elephant in the room, the problem

that seems to have caused the most frustration for the longest

period of time: The dreaded broken erasable-memory module,

B12!

Though not a part of the restoration team, I can feel the

frustration myself. For one thing, while you can't actually

do much with the AGC without a working erasable memory — after

all, software's raison d'être is basically to manipulate

the contents of memory, so if you can't do that, what can you do?

— you nevertheless can do enough to convince

yourself that the AGC would be almost completely operational if

only the memory were there. Like Moses gazing across the

River Jordan, you can see the Promised Land, but can't actually go

there! You see, internally to the AGC, even getting the

point where the first program instruction would be executed is a

very complex operation that the AGC can execute flawlessly without

memory, and which exercises almost every part of the CPU's

circuitry. You can even execute the first few instructions,

and can demonstrate that they work correctly other than their

affect on the broken 16th memory bit.

Another frustrating part is that the erasable-memory module is

one of the few potted modules, so that even if you can

determine more-or-less where the broken wire is, you can't get to

it to repair the break! That's not just because it's a

collector's item and you don't want to rip it apart, but also

because you cannot physically remove the potting material without

destroying the circuit.

At first, the team had the idea that if they could determine precisely

where the INHIBIT wire was broken, then perhaps they

could drill a small hole in the potting material to get access to

it, and then perform some kind of microsurgery through the tiny

hole to fix it. (This is the point where I had my sole

involvement, in digging up the mechanical drawings for the

physical configuration of the module, the specs for the potting

material and so on.) Rather than relying on my lame

descriptions, I'd recommend actually watching the team's video of

their attempt to find the break, and why they concluded that the

microsurgery idea couldn't work.

So, if you've followed the explanations above, you realize that

Jimmie Loocke and the restoration team now have a basically

restored AGC that is actually functioning, even though it has no

core-rope modules of its own. What else can you do with it?

You can do some trading! Or in the parlance of the day, you

can negotiate a deal.

Huh? What kind of deal? Well, for one thing, if

you've paid any attention at all to the things you've seen on this

website, you'll have realized that I'm mainly interested in

preserving the software of the AGC for future generations

and for the academic interest of understanding how the AGC

software evolved over time. But getting AGC software is a

tough proposition, since it usually depends on people who have

such stuff stepping forward and giving it to you. There

aren't that many people who can (or sometimes, sadly, who will)

do that. But wait, is there any way this nifty, now-restored

AGC can somehow be exploited to get some AGC software for us?

It turns out that there is! How effective it will be over

the course of time I don't know, but it works something like

this: There are various museums and even private collectors

who have AGCs. While those AGCs probably wouldn't function

if powered up, some of them may have core-rope modules in

them. And if you visit a museum/collector, taking along your

own now-functioning AGC, perhaps the museum/collector let you temporarily

install their own rope modules in your AGC, so perhaps you can

read the contents of those modules ... i.e., perhaps you can get

copies of the software the AGCs belonging to those museums or

collectors contain.

The fruits of that kind of wheeling-and-detailing (none of it by

me, of course, since I'm not a participant in the

restoration) are covered in the subsections below.

The Computer History

Museum in Mountain View, California, has an AGC. Their AGC has

core-rope modules installed in it, and those core-rope modules

contain a program called RETREAD 50.

The Computer History

Museum in Mountain View, California, has an AGC. Their AGC has

core-rope modules installed in it, and those core-rope modules

contain a program called RETREAD 50.The AGC itself uses this information merely to detect if there

has been memory corruption: If any single data bit

in a word has been corrupted, so that it has flipped from 0 to 1

or vice-versa, then the parity bit is wrong; the AGC can detect

the wrong parity bit. If two bits in a word have flipped,

then the parity doesn't change and the error can't be detected ...

but that's a much lower probability event, so the parity bit

provides pretty reliable detection of errors in most cases.

In our case, though, we can use the parity bit to actually fix

the broken memory bits! I mean, we can fix them in the data

file dumped from the core rope, and not in the physical core rope

itself.

How so? Well, in the case of the data read from the

Computer History Museum's core-ropes, we know that only a single

bit in some words is bad, and we know which bit it is, as

well. So all we need to do is to set those known-bad bits

(bit 14 in bank 0 or bit 3 in bank 4) in such a way as to make the

total number of 1-bits in each word odd. Simple! (Or

at least, simple for a computer! ![]() ) If two of the bits in any of the

words had been bad, we couldn't fix them this way (or at all!),

but with just one bad bit per word it works out perfectly.

) If two of the bits in any of the

words had been bad, we couldn't fix them this way (or at all!),

but with just one bad bit per word it works out perfectly.

Even so, that's not enough to give us confidence in the

data. For example, what about the fact that a random bit

here or there might have been corrupted sitting around the last 50

years or so? Those errors would normally be detected by

parity errors! Well, we can still use parity checking for

all of the core memory not affected by the systematic

errors. I mean, parity checking in all of the other memory

banks (other than banks 0 and 4) or in the 2nd halves of banks 0

and 4 is still just as useful as ever.

Another feature that would normally give us confidence is bank

checksums: In most AGC programs, each memory bank is

accompanied by a checksum word (basically the sum of all of the

other words in the bank), so if the checksum isn't consistent with

the other words in the bank, it's an easy way to detect

errors. Unfortunately, RETREAD is such an early program that

it didn't yet use bank checksums. So that's a

double-checking method that simply isn't available to us.

Another method of providing confidence of the data dumped from

the core ropes is to see if meaningful software source code can be

created for it. After all, the data dumped from the ropes is

just a series of numbers, the so-called "assembled" form of the

software source code. As such, it's nice to have and can be

used to run the program, but it's not really usefully

human-readable. Only the source code is readable, even even

if you need to be one of the illuminati to do so, so we really

want source code. One thing that assists in attempting to

come up with such source code is that RETREAD 50 is obviously

going to be very similar to RETREAD 44, for which we

already have the source code.

Indeed, the restoration team has gone through exactly this

exercise, by modifying RETREAD 44's source code as necessary to

get source code for RETREAD 50 than can, in turn, be assembled to

get precisely the (repaired) data dumped from the core

ropes. Not only that, I've been given a concise executive

summary of the differences between the two:

This RETREAD 50 code has been added on our LUMINARY page and in our

GitHub software repository for your delectation.