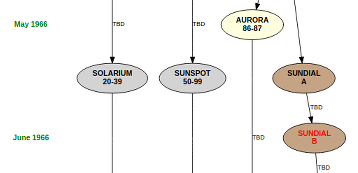

Programs with

names like Sundisk, Solarium, and Sunspot were pre-Colossus versions of the Command

Module AGC's software. They were not forms of Colossus as such, but provided

some code for Colossus.

If

you click on the image to the right, you can see a simplified family

tree for Colossus.

Programs with

names like Sundisk, Solarium, and Sunspot were pre-Colossus versions of the Command

Module AGC's software. They were not forms of Colossus as such, but provided

some code for Colossus.

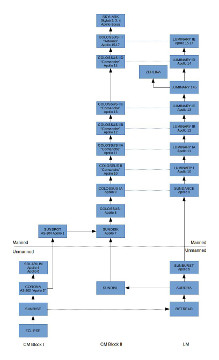

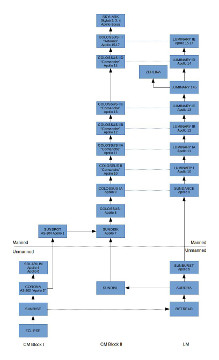

If

you click on the image to the right, you can see a simplified family

tree for Colossus. If you'd like to see a more

comprehensive but less CM-centric overview of all the available AGC

software source code and the manufactured core ropes than presented

on this page, you might want to look in the section of our Document

Library dedicated to AGC software listings. The diagram

to the right (click to expand) attempts to show the

interrelationships between every AGC software version (Luminary,

Colossus, or otherwise) and every AGS software version, along with the

documentation (Program Change Requests, memos, etc.) documenting the

changes. It covers literally thousands of versions and is

therefore very big!

If you'd like to see a more

comprehensive but less CM-centric overview of all the available AGC

software source code and the manufactured core ropes than presented

on this page, you might want to look in the section of our Document

Library dedicated to AGC software listings. The diagram

to the right (click to expand) attempts to show the

interrelationships between every AGC software version (Luminary,

Colossus, or otherwise) and every AGS software version, along with the

documentation (Program Change Requests, memos, etc.) documenting the

changes. It covers literally thousands of versions and is

therefore very big!| Mission | CSM number |

Mission Type |

CM Program | Revision | Source Code |

Other Mission-Specific

Documentation |

Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

TRIVIUM |

12/1963 |

Syntax-highlighted,

hyperlinked HTML Scanned page images |

N/A |

This is an unusual

program, in that its sole purpose was to demonstrate usage

of the original AGC assembler, YUL. In fact, its very

short program listing (only one page of source code!) that

was attached to a 1963 manual for YUL. The document

itself was obtained from the personal papers of the late

Russel Larson. |

| N/A | N/A | N/A | SUNRISE |

45 |

Syntax-highlighted,

hyperlinked HTML |

Apollo Mission

204 Reference Cards Keyboard and Display System Program for AGC (Program SUNRISE) The Compleat SUNRISE AGCIS #12A: Job Control and Task Control AGCIS #15: Block I Apollo Guidance Computer Subsystem AGCIS #16: Progress Control and Fresh Start and Restart AGCIS #17: KEYRUPT, UPRUPT, MARK and DSKY Functions AGCIS #22: Prelaunch Alignment SUNRISE 69 and Erasable Memory Test Program |

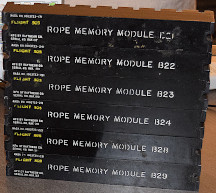

SUNRISE is a

program used for Block I system tests, providing a similar

service, I guess, to what the SUNDIAL program later provided

for Block II, and which AURORA provided for the LM. We

acquired SUNRISE 45 by dumping the contents of three

physical rope-memory modules to which an anonymous collector

gave us access. Now, it often happens that physical rope-memory modules are physically defective in one way or another, either as a result of sitting around for 50-60 years unused, or perhaps due to defective modules being more likely to have been discarded and thus more likely to have found their way into collectors' collections in the first place. Usually, due to fact that these memory modules have a 16th (parity) bit in addition to the 15 data bits at each memory location, these flaws are relatively easy to correct. The SUNRISE 45 rope is notable in that one of the three memory modules was rather more severely damaged than usual, but that Mike Stewart was able to deduce corrections for it anyway. We had a high degree of confidence in those corrections ... but still, they were unusually difficult to make, and we'd have even more confidence in the dumped data if those corrections hadn't needed to be made in the first place. |

| 69 |

Syntax-highlighted, hyperlinked HTML | The same comments

I made for SUNRISE 45 above basically hold equally well for

SUNRISE 69, with the difference that the that SUNRISE 69

spans four rope-memory modules rather than just three.

What's really interesting, however, is that the four memory

modules are the same three from SUNRISE 45, plus one

extra. If you think about it, that's pretty remarkable. After all, if the three SUNRISE 45 modules never access a 4th rope module, then how would the code in the 4th rope module ever be reached when you're running SUNRISE 69? The answer is apparently (and obviously, I admit) that there are verb/noun combinations that you can use in SUNRISE 45 to transfer control to an address in the extra rope-memory module, which is designated B22. (The first three modules are B28, B29, and B21.) For example, the SUNRISE 69 DSKY electroluminescent test is kind of fun, and it's started by the rather cumbersome command sequence, Whereas if you were to attempt the same thing in SUNRISE 45, it doesn't initiate the test. Rather, control is lost and all further key entries on the DSKY seem to be ignored. I'd expect that memory-parity errors would be encountered if this happened on a physical AGC, and that it would cause a system reset; since that doesn't happen virtually, I must not support parity checking in the CPU emulator. It sounds like the kind of thing I'd do. |

|||||

| Apollo 3 (AS-202) |

CSM-011 |

N/A |

Corona |

261 |

Syntax-highlighted, hyperlinked HTML | Document

Library |

Corona

261 is the Block I AGC software for mission AS-202.

Quoting from the wikipedia article: Corona

261 is the Block I AGC software for mission AS-202.

Quoting from the wikipedia article:"AS-202 (also referred to as SA-202) was the second unmanned, suborbital test flight of a production Block I Apollo Command/Service Module launched with the Saturn IB launch vehicle. It was launched on August 25, 1966 and was the first flight which included the spacecraft Guidance and Navigation Control system and fuel cells. The success of this flight enabled the Apollo program to judge the Block I spacecraft and Saturn IB ready to carry men into orbit on the next mission, AS-204."In other words, this is the first AGC software actually flown, and we can "fly" it too, at least in the sense of using it in the Orbiter spaceflight simulation system with the NASSP add-on. |

| Apollo 1 (AS-204A) |

CSM-012 |

N/A |

Sunspot |

≥247 |

On our wish list |

Yes, Apollo 1

never flew, but it certainly deserves a place of honor out

of respect for its crew. I'd sure like to know where

this program can be found! This was a Block I spacecraft. |

|

| Apollo 4 (AS-501) Apollo 6 (AS-502) |

CSM-017 CM-020 SM-014 |

A-1 A-2 |

Solarium |

55 |

Syntax-highlighted, hyperlinked HTML Scanned page images |

Apollo 4 and Apollo 6 were unmanned

missions, but it they did have working CSMs and working AGCs

in the CMs. Eldon C. Hall's copy of the AGC program

listing is in the American Computer Museum, which has

graciously allowed us to digitize the program listing for

use in Virtual AGC. These were Block I spacecraft. The "Programer"—yes, that's the real spelling, though some sources do refer to it as the "programmer"—was a gadget that was the stand-in for the crew. |

|

| 2TV-1 |

CSM-098 |

N/A |

Sundial |

E |

Core

rope dump Syntax-highlighted, hyperlinked HTML |

There's

a nice online writeup of the

2TV-1 mission that I won't paraphrase here, except to

say that it comprised four substantial (177 hours), crewed

missions that occurred entirely on the ground in June 1968. There's

a nice online writeup of the

2TV-1 mission that I won't paraphrase here, except to

say that it comprised four substantial (177 hours), crewed

missions that occurred entirely on the ground in June 1968."2TV-1" stands for Block II Thermal Vacuum no. 1, and more-or-less describes the missions, which were to subject the spacecraft to vacuum and to thermal shock whilst the astronauts did astronauty things. |

|

| Apollo 7 |

CSM-101 |

C |

Sundisk |

282 |

On our wish

list |

Unfortunately, we do not presently have

this software, which flew on Apollo 7. For further insights, note document E-2150, "Guidance, Navigation, and Control Block II Command and Service Module Functional Description and Operation Using Flight Program SUNDISK (Rev. 282)", whose preface reads: "The purpose of this document is twofold. The first is to provide a functional description (operationally oriented) of the CSM GNCS hardware and software and the interfaces with other SC systems. The level of detail is that required to identify and define telemetry outputs. Also included are functional flow diagrams of the Sundisk 282 programs and routines together with lists of verbs, nouns, option codes, and checklist codes for this flow. The second purpose is to provide the operational procedures for this hardware and software including malfunction procedures, and program notes. The nominal airborne expanded and condensed checklist for Sundisk appear in the Guidance System Operation Plan, R547." |

|

|

Apollo 8 |

CSM-103 |

C' |

Colossus

1 |

237 |

Syntax-highlighted, hyperlinked HTML Scanned page images |

Colossus 237 flew on Apollo 8. The Colossus 237 program listing was made available by original AGC developer Fred Martin. (Thanks, Fred!) The listing cuts off abruptly after page 1557—whereas you'd normally anticipate that there are 1700+ pages—so some of the assembler-generated tables at the end of the listing are missing. Of particular inconvenience, because it presents special problems for verifying the correctness of the simulation, is the absence of the octal listing and of the memory-bank checksums. However, all of the source code is present, and that's enough to work with. Note that we have a contemporary digital simulation of Colossus 237, though it only covers a bailout during burn (Colossus Software Anomaly Report #45, of which we unfortunately don't presently have a copy). By "contemporary", I mean that it's an Apollo-era simulation, and not one produced by the Virtual AGC Project. It is the only Colossus digital simulation available so far, although there are a number of Luminary digital simulations in our library, and as such it has a unique value. Specifically, it has pad-loads, though those pad-loads are for March 1969 rather than for December 1968. |

|

|

Apollo 9 |

CSM-104 |

D |

Colossus 1A |

249 |

Syntax-highlighted,

hyperlinked HTML The original raw scans, unprocessed |

Document Library |

Two separate sets of scanned images of the

Colossus 249 program, which was the CM software that flew on

Apollo 9, are available. They are from different

reproductions of the same original 1968 printout, as

owned by different AGC developers. Scanned image set

#1 is in far better condition than set #2 and is more

legible, and is the only one linked here. But only the

less-legible set #2 was actually available to me when I

originally implemented Colossus 249. Any hand-written

notes on the listings are from the original developers (as

far as I know), and so those notes differ on the two image

sets. |

| Apollo

10 |

CSM-106 |

F |

Colossus

2 (Comanche) |

44 |

Syntax-highlighted, hyperlinked HTML |

Reconstruction |

This is the

first software release of Comanche targeted for Apollo 10

whose rope-memory modules were manufactured. It is not

the version that was eventually flown in the mission. |

| 45 |

Syntax-highlighted, hyperlinked HTML | This is the second

revision of Comanche targeted for Apollo 10 with rope-memory

modules actually manufactured. It ended up not being

flown in the mission. |

|||||

| 45/2 |

Syntax-highlighted, hyperlinked HTML | This is the third

and final revision of Comanche for Apollo 10, and is the one

actually flown in the mission. I should clarify that

strictly speaking this is not a revision of

"COMANCHE". Instead, it is a side development branch

that split off from COMANCHE at COMANCHE 45, and is actually

called "MANCHE45", thus if we had the printout of the

original assembly listing (which we do not), at the tops of

the pages it would say "REVISION 002 OF PROGRAM

MANCHE45". The reason for this is that it allowed

Apollo 10 development to continue with MANCHE45 rev 1 and

rev 2 while Apollo 11 development was independently going on

with COMANCHE 46, COMANCHE 47, etc. |

|||||

| Apollo

11 |

CSM-107 |

G |

Colossus

2A (Comanche) |

51 |

Syntax-highlighted, hyperlinked HTML | Comanche 51 was

the software release initially intended to be used

in the Apollo 11 Command Module. Its rope-memory

modules were manufactured. However, there were

subsequent revisions to the software before the mission

occurred, so Comanche 51 never flew, and Comanche 55 (see

below) did instead. |

|

| 55 |

Syntax-highlighted,

hyperlinked HTML Scanned page images |

This is the 2nd and final revision of

Colossus for Apollo 11, and is the one actually flown in the

mission. |

|||||

|

Apollo 12 |

CSM-108 |

H-1 |

Colossus 2C (Comanche) |

67 |

Syntax-highlighted, hyperlinked HTML |

Document Library |

This is the CM AGC

software flown on Apollo 12. While we have no contemporary source-code listing, we've obtained an accurate core-rope image of Comanche 67, dumped from physical core-rope modules of an anonymous collector. I'm told that from the serial numbers of the modules, they appeared to comprise a spare flight set. (Thanks, Anonymous!) Mike was able to quickly regenerate Comanche 67's source code — albeit, as always, with a proviso that program comments and other features of the source code that aren't reflected in the core rope may inaccurate. |

|

Apollo 13 |

CSM-109 |

H-2 |

Colossus 2D (Comanche) |

72 |

Syntax-highlighted, hyperlinked HTML | Document Library |

Comanche 72 was the first revision of the CM

AGC software targeted for Apollo 13 that was actually

manufactured into core ropes. It wasn't flown,

however, with that honor instead going to revision 72/3 (see

next entry). While we have neither the contemporary software listing nor a dump from the contents of physical core-rope memory modules, Mike Stewart has fortunately been able to reconstruct the source code for it, using as source material the original program-change notices (from Comanche 67 to Comanche 72), the physical dumps of Comanche 67, the source code from related versions, and other materials. The very-detailed notes of this process are here. There are two significant things to know:

|

| 72/3 |

Syntax-highlighted, hyperlinked HTML | This is the CM AGC software flown on Apollo

13. Strictly speaking, it's not actually COMANCHE at

all, but rather is a development branch called MANCHE72 that

split off from COMANCHE at COMANCHE 72. The idea is

that bug fixes or other changes strictly for Apollo 13 could

be made in MANCHE72 rev 1, rev 2, and rev 3 while changes

strictly for Apollo 14 could continue to be made

independently in COMANCHE 73, COMANCHE 74, COMANCHE 75, and

so on. This is a technique you use in

strictly-controlled software to avoid unintentionally mixing

in changes for one mission with those from another.

You see, all changes have to be approved by a so-called

"control board", and changes are typically approved for

specific missions rather than willy-nilly blanket

approvals that affect lots of missions at the same

time. Thus if we were lucky enough to have a printout

of the assembly listing (which we do not), at the tops of

the pages it would say that this is "REVISION 003 OF PROGRAM

MANCHE72", and would not mention COMANCHE at all. We currently lack a contemporary assembly listing or physical memory modules of MANCHE72R3, but since there was only a single approved change vs Comanche 72, reconstruction of the source code was relatively easy. (I'm told!) And the documentation of the reconstruction process (see here) is certainly much smaller than that of Comanche 72. The reconstruction does inherit the "Cosmic Spoonerism" problem of the Comanche 72 reconstruction, but I don't think that that detracts from the confidence we should have it. I'm told also that some tests have been performed on the reconstructed MANCHE72R3 in Orbiter/NASSP, but there are no fully-flown missions or videos from simulated missions to report to you as of yet. |

|||||

|

Apollo 14 |

CSM-110 |

H-3 |

Colossus 2E (Comanche) |

108 |

On our wish

list |

|

This is the CM AGC

software flown on Apollo 14. Although we don't presently have the Apollo 14 CM software, Niklas Beug, a developer and user of NASSP, the Apollo-mission add-on for the Orbiter spaceflight simulator, tells us that it's actually possible to use a modified form of Artemis (the Apollo 15-17 software) to fly satisfactory Apollo 14 missions. Let me simply quote Nik: We currently don't have any AGC version available that was flown on Apollo 14, which causes a few, mostly procedural issues for NASSP. Apollo 14 was the only mission flown in the time period from July 1st, 1970 to July 1st 1971 and as such used a slightly different coordinate system than the AGC versions before and after that. And using a different coordinate system means that a few hardcoded constants had to be changed every year: star unit vectors, solar and lunar ephemeris in the LGC and a few other numbers. These numbers for the yearly coordinate system used by Apollo 14 are available or can be calculated. So we did just that and created our own AGC versions for Apollo 14. Both CMC and LGC are derived from the AGC versions flown on Apollo 15, Luminary 1E and Artemis (Colossus 3). We determined that these most closely match the programs and capabilities of the AGC versions actually flown on Apollo 14. One regular NASSP user (Alex Bart, ...) tested Apollo 14 with these modified AGC versions and flew the complete simulated mission with them. We are very confident now that these AGC versions are working as they should. As I said, they are essentially still the AGC versions flown on Apollo 15, only slightly modified to properly work with Apollo 14. ... They are available here, as Artemis072NBY71.bin and Luminary210NBY71.bin, [i.e.] Artemis072 and Luminary210 modified to work for the Nearest Besselian Year (NBY) coordinate system of 1971.Unfortunately, "reconstruction" of the source code for Comanche 108 in a similar fashion to some of the other software versions you see in this table isn't very likely. The reason is that unlike the software versions which have been (or may yet be) reconstructed, we do not know the memory-bank checksums for Comanche 108; thus even if by some chance the code were to be reconstructed perfectly, we still would not have any assurance whatever that the reconstruction was correct. And without that assurance, why would anyone use it rather than using Artemis? So there's little point even attempting a reconstruction other than as a pure intellectual puzzle. On the other hand, for all I know, a software listing or core-memory-module dump for Comanche 108 could suddenly appear, thus changing everything. That would be lovely. In lieu of that, with apologies to the Baroness Orczy, We seek it here, we seek it there, |

| Apollo

15 |

CSM-112 |

J-1 |

Colossus

3 (Artemis) |

71 |

Syntax-highlighted, hyperlinked HTML | Document Library |

Artemis 71 was the

first revision of Colossus targeted for Apollo 15. Its

rope-memory modules were manufactured, but the program was

subsequently revised and Artemis 72 instead flew in Apollo

15 through 17. We do not have a copy of one of the original Artemis 71 program listings, but it turns out to be possible to reconstruct its source code with confidence from the source code for Artemis 72. Mike Stewart (thanks, Mike!) has done so, and has provided an instructive full writeup of how he figured it out. |

| 72 |

Syntax-highlighted, hyperlinked HTML Scanned page images |

Document Library | This is the 2nd and

final revision of Colossus, flown in Apollo 15, Apollo 16,

and Apollo 17. Also known as Artemis build 072, released (Fabrizio Bernardini tells me) January 31, 1971. A private collector has graciously allowed us to digitize this program listing for use in Virtual AGC. |

||||

| Apollo 16 |

CSM-113 |

J-2 |

Document Library |

||||

| Apollo 17 |

CSM-114 |

J-3 |

Document Library |

||||

| Skylab

2 |

CSM-116 |

N/A |

Skylark |

48 |

Syntax-highlighted, hyperlinked HTML |

Document

Library |

The

Skylab 2, Skylab 3, Skylab 4, and ASTP

missions all used the same Skylark 48 software for the

Command Module's AGC. While we do not have a contemporary listing

of Skylark 48's source code, we do have dumps of the physical core-rope

memory modules actually flown on the Skylab 2 mission from the New Mexico Museum of Space History;

many thanks to the museum and Executive Director Chris Orwoll for

allowing Mike to dump these modules, and to Larry McGlynn who

facilitated! You can see a photo (click to enlarge) of Mike's

setup for dumping the contents of the modules at the right. The

Skylab 2, Skylab 3, Skylab 4, and ASTP

missions all used the same Skylark 48 software for the

Command Module's AGC. While we do not have a contemporary listing

of Skylark 48's source code, we do have dumps of the physical core-rope

memory modules actually flown on the Skylab 2 mission from the New Mexico Museum of Space History;

many thanks to the museum and Executive Director Chris Orwoll for

allowing Mike to dump these modules, and to Larry McGlynn who

facilitated! You can see a photo (click to enlarge) of Mike's

setup for dumping the contents of the modules at the right.For some reason — I guess you use what you have! — the museum stores and/or exhibits the core-rope memory modules as housed within the actually-flown AGC from the Apollo 15 mission: Mike Stewart has reconstructed the Skylark 48 source code via the usual process of adapting source code from elsewhere (such as Artemis 72) until reaching a point where the recovered source code assembles identically to the module dumps. Which makes it all sound very easy and straightforward ... though you have to know that it's not! Of course, the dumps of each module individually are also available in our Rope Module Dump Library, so you can try your own hand at reconstructing the source code if you're feeling particularly cocky. And as usual, you can run Skylark in our AGC emulator; in the VirtualAGC GUI wrapper of the AGC emulator, for instance, just select the Skylab 2, 3, or 4 mission, or the Apollo-Soyuz mission. See also the Programmed Guidance Equations document (part 1, part 2, part 3). |

| Skylab 3 |

CSM-117 |

Document Library |

|||||

| Skylab 4 |

CSM-118 |

Document Library |

|||||

| Apollo-Soyuz Test Project |

CSM-111 |

Document Library |

| Filename.agc |

Source code for major subdivisions of the Colossus program. |

| MAIN.agc |

Organizer which treats

all of the other assembly-language files (*.agc) as

include-files, to form the complete program. |

| Filename.binsource |

Human-readable form of

the binary executable as an octal listing. |

| Filename.bin |

Binary executable created

from binsource (octal listing) file. |

Technically speaking....A point which may not be completely appreciated is that Colossus249.bin was not created from the assembly-language source files. Therefore, the byte-for-byte equivalence mentioned above actually has some significance. In fact, both the assembly-language source code and Colossus249.bin (or Colossus249.binsource) come from separate readings of the original Colossus assembly listing scan, so their equivalence provides an important check on validity. (See below.) The file Colossus249.bin was created from the human-readable/editable ASCII file Colossus249.binsource by means of the program Oct2Bin, with the following steps: cd Colossus249

../Luminary131/Oct2Bin <Colossus249.binsource mv Oct2Bin.bin Colossus249.bin Admittedly, few people are likely to perform any processing of this kind unless contributing a new version of the Colossus code to the Virtual AGC project. |

Thus while we can't have as much confidence in the validity of

the Colossus 237 transcription, in comparison to almost all of

the other Colossus and Luminary transcriptions, the code has

nevertheless been double-checked both manually (visually) and in

an automated fashion as well.